|

|

Anne Murphy − The Letter |

|

The framed collection of memorabilia sits unhung, propped up on a bookcase in the study between a bronze statue of a Royal Marine Commando in Winter Warfare combat equipment and a pencil portrait of a woman in uniform, complete with beret. Behind the glass frame are mostly black and white photographs of the same woman, shown from childhood to old age, alongside a row of medals and a letter, typed in the finest British tradition. |

|

|

|

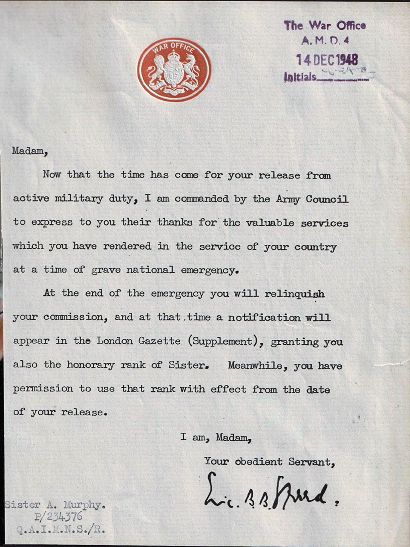

The letter is embossed 'War Office' and sits on yellowed, by design, A5 sized official paper. The illegible signature of some long forgotten Civil Servant ends the letter, signing off as an 'obedient servant' which belies the effect the letter must have had on its intended recipient. In the bottom corner the designation 'Sister A. Murphy, P/234376 Q.A.I.M.N.S./R.' is faded and had been typed almost as an afterthought, perhaps because there were so many similar letters. The ink is a shade of grey lighter than the main body, similar in colour to the passport sized and styled photograph of a smiling short haired soldier placed alongside it. |

|

The 'Sister A. Murphy' referred to was born Annie Murphy on 14th August 1909 in the parish of Cockpen in Midlothian. Known as Anne throughout her life, she was one of five girls and two boys born to parents who were mining folk, having themselves been born into the same. Almost a tradition. Anne's early life, in this most rural area, meant she and her siblings were protected from the worst of the Great War in 1914 but at five years old, something she, and her sisters, saw or heard influenced them and there was no question that when another war loomed, they would serve, and survive, unlike many of their countrymen. The letter, in 1948, may have been hand delivered or posted to a hospital or camp, there is no envelope. It has a purple inked stamp in the top right corner indicating the department it was sent from – A.M.D.4 – and the date 14 DEC 1948, as well as the initials of the typist's supervisor who authenticated the text. The date is significant as it is three years after World War II had ended. AMD4 or Army Medical Department [number] 4, there were many, had been set up originally in 1914 and was responsible for the administration of British Military Nursing Services. Operating like a well oiled machine it ran from the depths of the imposing Adastral House at 61 Aldwych, in the centre of London. The building had previously been occupied by the Air Ministry, who had submitted to Governments intervention to enable rooms to be given up to other arms of the services and their many support civilians. The clerks and typists who populated the rooms and corridors, themselves wives, husbands and sweethearts of serving armed forces personnel, composed the correspondence sent to individuals and families, advising of personnel status or giving orders, many times using words that were difficult to type but even harder to receive. Anne and her sister Mary had been nursing for ten years at the beginning of the 'grave national emergency' that became another world war and both had enrolled in Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserves so the move from inactive (but practising) reservists to serving and 'active' military personnel at the beginning of the war was seamless. Youngest Sister Helen joined them later but although all three were similarly trained professionals, they were rarely able to serve together in the same place and would instead find themselves scattered across North Africa and Europe during some of the bloodiest battles man had known. Initially the sisters remained in Britain to help treat the injured soldiers, sailors and airmen returned from foreign battlefields with horrific injuries caused by bullets, bayonets and bombs, some still bleeding and broken and, as-often-as-not, missing limbs. The work was horror filled but the young men and women were strong and fought to get better so most were saved, sometimes from themselves, then sent home to their waiting loved ones for recuperation. In July 1942 Anne Murphy was commissioned 'Sister' in the QAIMNS/R, a branch of the military first formed in the Crimea in 1854 when Florence Nightingale took 38 women to work as nurses and nursing attendants at Scutari Hospital in Turkey. In 1943 Anne travelled by ship, via the Horn of Africa to join the allied troops in the north of the country. Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, had begun just months before and after allied landings at Casablanca, Algiers and Oran, Field Marshall Montgomery pushed his troops hard to destroy the occupying forces of General Erwin Rommel and the might of the German Army. Casualties were inevitable and because the aid stations at the beach heads overflowed quickly, casualties were moved rapidly by hospital train to Bone [now Annaba] for evacuation by sea. At thirty four, Anne was almost ten years older than most of her patients and sometimes when darkness fell in the quickly cooling desert and lights were dimmed in the tents, her baggy khaki battle dress and army boots meant she was often mistaken for a male doctor or orderly, only the stars glinting off her pips gave her rank and position away. |

|

"The Penicillin injections alone would keep members of the staff busy on each ward, as they had to be given 3-hourly day and night, and it was possible to have as many as 35-40 in one batch". Annie Hughes QAIMNS. |

|

Although sprightly, climbing the three feet into the converted cattle railway cars was awkward but manoeuvring stretchers without tipping the disabled patients off onto the hard and sandy ground, a real struggle, and in many cases frightening. The ensuing journey to Bone was not long but the temperatures in the cars could exceed thirty degrees centigrade during the day with seventy-five percent humidity which exacerbated cases of heat stroke. Travel at night saw the other extreme as it cooled rapidly to as low as eight degrees and additional blankets were required. The rancid smell from those poor souls with dysentery meant that doors had to be kept open unless sand storms. |

|

"It was routine treatment to put all these casualties on to Sulphonamide, and a good system of cards is now in use for this and Penicillin, so that a course, once started, can be checked and dated at each stage of the journey and the patient is not kept waiting for the rest of his course until he gets to Base". Annie Hughes QAIMNS. |

|

forced closure so there was only limited reprieve. Moving externally between cars, Anne could occasionally see campfires amongst the palm trees silhouetting camping Tuareg people at their overnight stops and wisps of charcoal and spices entered the carriage, misleading her senses. Anne moved into the European Battlefield and her sister Mary to Sicily but as the Victory in Europe (VE) day came and went, her services were required nearly four thousand miles away in Agra, India, where with many Indian colleagues and patients, she continued to dispense aid to the needy under very trying circumstances at the Bareilly Military Hospital. In late November 1947 she returned to a warmer-than-usual but still bitterly cold, compared to India, England to continue her vocation as a nursing Sister-in-Charge of the Medical Division in the Military Hospital, Barming Heath near Maidstone in Kent. The nine officers, 15 Nursing officers (of which Anne would be one) and 104 other ranks maintained the declining admissions as invalids and troops in the surrounding areas were dispersed to other bases and home. Morale was maintained by steadily moving staff to leave periods and for those who stayed, dances and sport were returning to what could be classed as normal. The live in patients here enjoyed Anne's cheerful disposition and her subordinates benefited from her vast knowledge and ability to instruct them but as hospital staff and patient numbers dwindled, Anne realised that at some point, soon perhaps, her services in the military would end and in military jargon she would be surplus to requirements. Eventually 'the letter' arrived. Officially addressed and stamped in the formal method reserved by the military, for the military. It may have been left unopened for a day or two but eventually Anne had to open it. Was it a shock or unexpected? I think not. It was not in Anne's nature to look back but it did have an impact. After reading it, she kept it with her other treasured possessions for the rest of her life, over forty years. It signified the end of a long, and on many occasions, hazardous journey which she had survived. The memories it held were all-important to her. After demobilisation, she returned briefly to her home in Edinburgh where nurses were in great demand but after only two years, early in 1951, she signed up again during the Korean emergency and was commissioned Captain in the QARANC, Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corp. Her period of service during this time is yet to be researched but in any event by 1955 she was a civilian at last and had become the District Nurse in Kirkmichael, Perthshire where she roamed the hills and glens on her bike then car, dispensing laughter and medicine in equal doses and overseeing births and deaths until her retirement in 1974, aged 65. When she died in 1990, the letter came to light amongst her possessions. At eighty one she had lived a full and glorious life, explained in detail in Alan Dunsmore's articles in the Peoples Journal in 1970. She had moved from the small village of Kirkmichael where winter snow drifts were impenetrable and could last for weeks, into the friendly, bustling town of Blairgowrie where she walked her dogs along the braes overlooking the fields of raspberries the town is famous for. I'm sure she knew everyone, certainly everyone seemed to know Anne. |

|

|

|

Written by: Frank T Connelly, 19th August 2021 References: |