|

|

Bernard Connolly − Immigrant (c1840 − 1874) |

|

Just as the last sentence was passed in the United Kingdom for being hung, drawn and quartered, Bernard Connolly was born in Ireland circa 1840. Bernard´s parents, Barnett and Bridget (nee Ward) were both in their twenties having both been born in Ireland some 20 years before. There may have been other children but no records have yet been found. His father Barnett´s life as an agricultural labourer would have been hard toil. Most of the land was owned by English landlords and the land tenant, or worker, farmed it for meagre wages. Working days were long and back breaking. Average life expectancy was 40 years. |

|

|

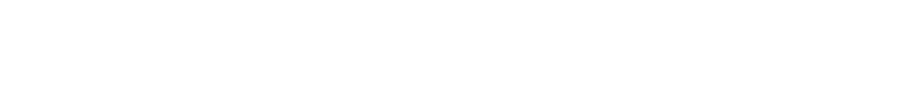

Sunlight and Shade. Poems and pictures of life and nature. - Illustrations by F. Barnard |

|

Baby Bernard´s early life passed wrapped in blankets or shawls for protection, for even inside their home, conditions were poor. A typical land workers rented house of the time would have been made of simple stone, mud, earth sods and scraps of available timber. These houses were sometimes grouped into little village areas called ´clachans´. A single room with a hearth where a large pot sat for cooking their vegetables was the hub of the home. Above the hearth sat a chimney hole, to let the woody smoke out and the single wooden door made from timber scraps was the last protection the family had from the elements. These hovels were draughty and damp with the family sleeping in one spot near the fire for warmth. Baby Bernard may have had a small wooden cradle bed, although furniture was scarce. |

|

|

Cottage, Achill Island, Alexander Williams (1846-1930) - Museum of Great Irish Hunger collection (Quinnipiac). |

|

Outside the front door, household waste was deposited in a midden (or compost heap) which meant the smell of dung from that and any animals, which would also have been kept in the house, would permeate the air. From the outside, during warmer weather these ´hovels´ , which dotted the Irish landscape, would have appeared to be ´gently steaming´. Such poor conditions would also mean that illness was common, typically amongst poorer people, who were badly housed, under nourished and lacked basic hygiene and would have been more susceptible to typhus or cholera. Little wonder many children died in infancy. Young Bernard´ s early life was spent for the most part with his mother until of an age where he would benefit from education. The family was catholic and this would later affect his schooling but almost before he started, disaster befell. The ´Great Famine´, also called Irish Potato Famine between 1845 and 1849 was a disaster that affected other countries as well as Ireland. The disease destroyed both the leaves and the roots, or tubers, of the potato plant making them inedible. The Irish famine was the worst to occur in Europe in the 19th century. Because the potato plant was hardy, nutritious, calorie-dense, and easy to grow in Irish soil, by the time of the famine, nearly half of Ireland´s population relied almost exclusively on potatoes for their diet, and the other half ate potatoes frequently. The consequences when the crops failed were therefore devastating across the globe. |

|

Coping in crisis Although the potato crop had failed, Ireland was still exporting tonnes of food to Britain to the profit of English and Irish landowners who claimed the right to what food remained after the crop failure. Peasants found eating the crops they had grown with their own hands were often accused of theft, or "poaching" the landowners´ game, which sometimes even included vermin, like mice. There were cases of starving Irish peasants being hung for poaching. People lived off what they could forage including wild blackberries, green grass, old cabbage leaves, as well as other wild-growing food like nettles. These barely staved off their nutritional needs and many tried to eat the diseased potatoes but this made them even sicker and death sometimes followed. Bird´ s eggs and fish were rare depending how quick or close you were to the nests and seas. An observer at the time, in 1846, wrote the following in a letter to the Prime Minister: |

|

"For 46 years the people of Ireland have been feeding those of England with the choicest produce of their agriculture and pasture; and while they thus exported their wheat and their beef in profusion, their own food became gradually deteriorated until the mass of the peasantry was exclusively thrown on the potato". |

|

Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel decided to establish a Temporary Relief Commission, separate from the poor law. This commission would set up local committees which would hand out food to the poor, and establish a system of public works. In secret, Peel arranged for a large shipment of cheap Indian corn from America. It was thought that the full impact of the potato shortage wouldn´t be felt until the next spring and summer, giving plenty of time to set up the relief efforts, and to have the Indian corn in place as a replacement for the potatoes. Peel hoped the corn would help get the Irish poor off of potatoes but it needed proper cooking and many failed to do this and exacerbated the problem again. Family members who died were not always moved as others were too weak. Even then bodies were buried close to housing and barely beneath the soil, attracting vermin and causing more disease. Flea-bitten rats, dogs, and other rodents ate the bodies. Most fatalities came about not from starvation itself, but the diseases associated-including ´The Black Fever´ which travelled from person to person by skin lice, making the skin black and was fatal to all that contracted the disease. In 1847 the British Government began to help those affected by the famine by setting up soup kitchens and programs of emergency relief but this fell through when a banking crisis hit Britain. This caused them to rely on work houses, even though they had never planned on using these to deal with the disaster. Around 2.6 million Irish had to go to overcrowded workhouses and this resulted in more than 200,000 deaths. Getting away from this awful place must have been like a distant dream to the Connolly family but at some point either during or just after the famine (before 1867) that is exactly what they did so whilst young Bernard was getting his first schooling, Father Barnett and mother Bridget were planning their escape. It´s a school Although the penal laws of 1695 had been repealed, the purpose of them had been to stifle catholic teachings and thus prevent Catholics coming to power. In fact it was illegal to send catholic children to school and Catholics could not become teachers. By sending the children to protestant schools it was hoped they would learn to be loyal to the crown of England, would learn the English language and would adopt the Protestant faith. His introduction to education may have been at a ´ Hedge´ school. These secret schools were set up for Catholic and other "non-conforming" children. These were called 'scoileanna scairte' in Irish. |

|

|

hedge School |

|

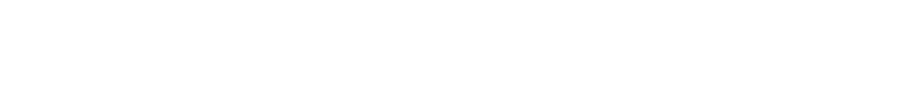

Many parents still continued to send their children to hedge schools up until about the 1840´s. After the end of the penal laws these schools did not have to be such temporary dwellings in hedges. Some hedge schools were also in places like cow sheds, mud cabins and some were built of sods by the parents of the children. They were often damp and wet so even escaping the damp draughty home there was no escaping the elements for Bernard. His daily barefoot trek to school with others from the village around him must have seemed fairly normal at the time. Perhaps he carried peat or stick supplies for the school fire or something for his lunch and most likely he and his young playmates kept an eye out for berries and eggs and other food stuffs along the way. There would be few men working in the fields around him other than to dig up the blighted potatoes to earn a pitiful wage. As the daily trek in the changing weather stretched over weeks then months he would have witnessed changes in the farms around him with the introduction of new, standardised farm machinery. This included the introduction of the all-metal ploughs, reaping machines or horse drawn potato diggers. Changes which would make massive and irrevocable differences to his father´ s labours. |

|

|

Children carrying turf to school |

|

Emigrating Did his father and mother sit him down to tell him they were emigrating or maybe they took him out for a walk one day and never went back to their dank home? Their few (if any) possessions would not have taken up much space and although we currently don´ t know if there were other family members, it would not have been difficult to make up an excuse. But what an adventure when they reached the port! With fares from as little as 6d for a deck passage from Ireland to Greenock, emigration to Scotland was a regular feature of Irish life even before the 1840´ s. Unlike those Irish emigrants who set sail for Canada, the USA, Australia and New Zealand, passengers leaving Ireland on ships to England, Scotland and Wales were not counted or recorded on embarkation or disembarkation. Most of the emigration, however, was on a temporary seasonal basis, peaking during important times in the farming calendar, such as harvest. |

|

|

Belfast Steamers |

|

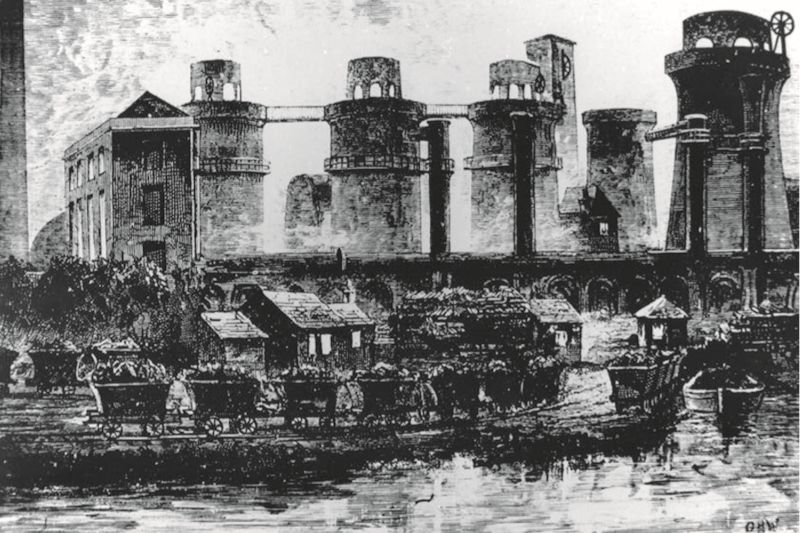

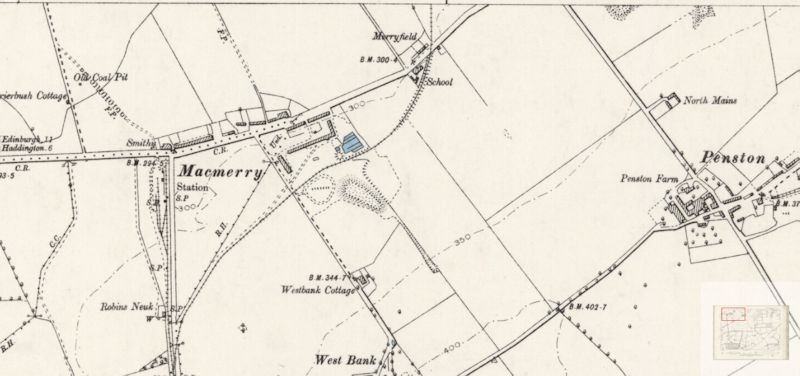

Because of their poverty and poor state of health, Irish immigrants tended to settle in or around their point of disembarkation which, in practical terms, meant the west coast of Scotland. The nearest counties or shires to Ireland -Wigtownshire and Kikcudbrightshire - had substantial Irish populations. The Irish also made their way to the east coast, particularly to Dundee, where a large female Irish community established itself. Edinburgh had only a small Irish community in 1851, so what made the Connolly family settle there? Possibly another family member or friend had gone ahead some time before and finding work, had settled. Although there were periods and areas of resistance to their arrival, the Irish found it relatively easy to find work, mainly because they were willing to take on gruelling work, often in harsh environments. While the work was hard and unskilled, it was not necessarily poorly paid. It is true, however, that many of the dirtiest, least healthy and most dangerous jobs seemed to recruit a disproportionate number of Irish. Bernard´ s job as an Ironstone Labourer in 1864 seems to bear this out. Bridget at this stage of her life might also have worked. Maybe working with her husband, also at the Ironworks but there was also a significant number of Irish street selling or hawking even as late as 1911 when it accounted for nearly 9% of working females. Working from barrows, hand carts or baskets, they sold fruit or flowers, brushes and matches and other small household items. Settling in to a new life. Finding work was key and Bernard was no stranger to hard labour. He may have trained as a blacksmith before leaving Ireland as actual dates are currently unclear. His wife to be, Jane McDade (born c1840 in Donegal) was a resident of the small Southfield community near the Ironworks at Gladsmuir in East Lothian and may have introduced him to someone at the works or met him during his first few days and fallen in love. Ironstone and the ´ Great Iron Rush´ In the 19th century the parish of Gladsmuir (Originally called ´ Gledsmuir´ (the moor of the kite or hawk)) where Bernard Connolly worked was an industrial area, rich in clay and iron and also with limestone and coal deposits. Nearby Samuelston and Longniddry were weaving villages, and there were iron works at Macmerry (´ the Blast´ ) and limeworkings at Harlow. Bricks and roof tiles of a distinctive white colour were produced locally. The main Edinburgh to London road ran through the parish, and later the railway lines to North Berwick and the south also passed through. Whilst the most valuable deposits of ironstone were located in Lanarkshire and Ayrshire with the majority of the ´ pig-iron´ made in Lanarkshire, they were not the only deposits to be found in Scotland. In February 1868 it was reported in the Haddington Courier that Sir Thomas Hepburn of Smeaton had recently begun to work ´ what promises to be a very valuable deposit of Haematite iron ore´ from the Garleton hills on his farm in West Garleton, 1 mile north of Haddington. Initially, a 50 yard wide 200 yards long seam was opened on the hillside quarry (the remains of which can still be seen today) and leading iron companies from across the United Kingdom visited to inspect and bid for the lease which they hoped would allow quarrying for up to 5000 tons per annum. A & C. Christie, local businessmen, were successful bidders. The local press reported that they had gained what was in effect ´one of the richest and most valuable discoveries in Scotland´. From the quarry at Garleton, ore would be transported by cart approximately 6 miles along rutted tracks to ´the blast´ at Gladsmuir, thereafter the ´pig-iron´ would be moved to the Ironworks at Tranent for working, or even further by rail to the great ironworks in the west, including Gartsherrie in Lanarkshire. Only three years later, towards the end of a long drought in the summer of 1871, the surface materials had been ´ worked out´ by the 30 or so miners who toiled night and day (except Sundays) so shafts were sunk and a steam engine put up to help extraction. Shafts, some 7 feet in diameter, were sunk as far as 200 feet down in the hope of continued prosperity but alas the Christie´s, who also owned the Gladsmuir Blast and a local brick and tile works, lacked the necessary expertise to operate commercially so gave up the lease. The Coltness Iron Company took over and had grand plans, including the erection of additional cottages for labourers, but by 1874, even after importing ´professional´ miners from Cumberland; they too had succumbed to foreign imports and so closed the largely unsuccessful quarry. At it´s peak, the UK industry employed some 13,000 miners just to get the materials out of the ground but once the cost of importing ore (initially from Sweden) dropped lower than was achievable in the UK, the industry withered and mines began to close. Blast Furnaces were large circular tower like erections. Narrow at top and bottom, lined with fire brick and ganister (close-grained, hard siliceous rock) around which is a ring of loose material, an outer masonry wall and enclosed with iron sheeting. Between 40 − 100 feet wide and as high, with an internal capacity of up to 25,000 cubic feet were common. Once lit, the ore was fed in from the top of the tower and when melted, was drained from the bottom onto a sand-bed into which had been drawn channels called ´sows´ and ´pigs´ (hence the expression ´pig-iron´) where the molten metal was left to cool. |

|

|

Summerlee Ironworks, Coatbridge. Mid Nineteenth century - Society of Antiquaries of Scotland |

|

The ´blast´ at Gladsmuir had at least 2 towers with a number of associated buildings including a water reservoir (see map below) and a smithy, as well as producing (over time) a large slag heap. Foundry conditions saw dense clouds of smoke roll over ´ the blast´ continuously, resulting in a dingy aspect to the local buildings. A coat of black dust lay on everything, and in only a few hours, visitors complexions would have considerably deteriorated by the flakes of soot which fill the air. At night, ´ great lurid flames belched out´ from the towers and could be seen for miles. |

|

|

Iron Foundry and ´slag´ heap to the east of MacMerry - NLS OS map 1892 |

|

Bernard, the Furnaceman, operated with the Blast Furnace. The job involved mixing raw materials then loading ´the blast´ from the top, with alternative layers of iron or ore, and the charcoal or coal. The forced flow of air was controlled, and the resulting molten iron then drawn off from the bottom of the tower and channelled into moulds. It was a continuous process so he worked shifts where he was exposed to choking dust, high temperatures, noise, and chemical substances. Even though he was required to be ´ overall fit and with fast reactions´ , accidents were not unusual, and Jane regularly treated burns to his hands and face Wages On a beautiful day on 29th July 1864, Bernard and Jane married in Portobello, near Duddingston in Edinburgh. The parish church of St John´ s is still the family church 150 years later with many family members living in the vicinity. This would not have been the nearest church to their home in Gladsmuir so another connection still remains to be uncovered. Barnett and Bridget must have looked on proudly as their son and new daughter-in-law took their vows and then celebrated like only the Irish can, late into the night. And celebrations continued with the patter of tiny feet just 9 months later when their first son James (15May 1865 − 1 Feb 1927) was born. Granny and Grandpa (Barnett and Bridget) must have been over the moon as within just a few short years, the families survival of the famine had been so beautifully eclipsed and surpassed with three more siblings arriving in short order: Mary on 26 July 1867, Alexander 27 December 1869 and Hugh on 14 June 1872. Alas this oasis of calm and plenty would end quickly as both Barnett and Bridget passed, followed quickly by a still young Bernard. Whose death aged just 34 on 11 September 1874 at 14 Drummore, New Row, Inveresk, near Edinburgh, from inflammation of the intestine, devastated the family. Four children under ten left with a young mum would have made life almost intolerable but the family thrived and Jane lived on until she was 55, moving eventually to Eastern Duddingston, near the church where they married and started their life together. |

|

Sources: |

|

Frank T Connelly October 2019 |